Was tough doing this in camp, but I’m finally done. It’s rare to see someone’s thought process for an entire paper, so here’s mine – hopefully it’s sufficiently entertaining.

Needless to say, spoilers below.

Here we go again!

(0h0m) First thoughts:

- Ok GCA. Is that an FE?! What kind of word is aquaesulian?

- Why is the easy geom so long?

- Why is Q5 so long?

- This paper actually looks bad, let's see how it goes..

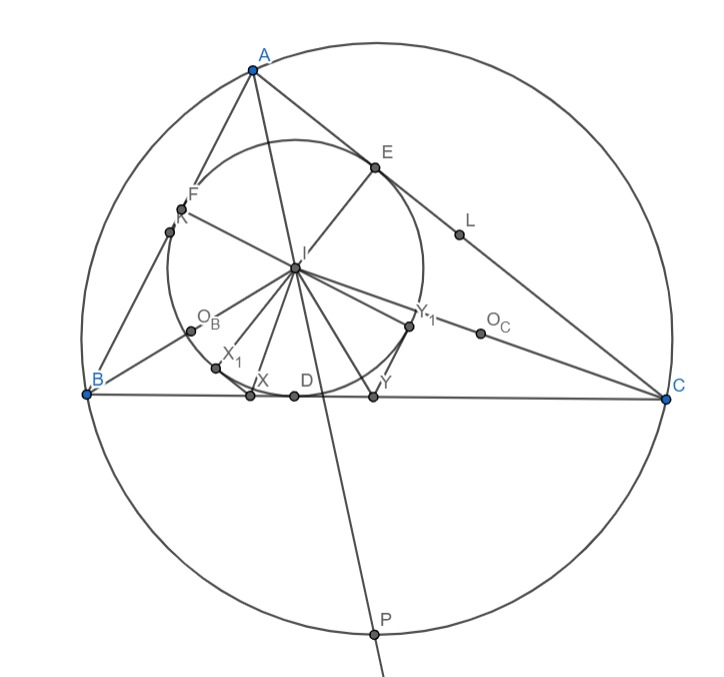

(0h5m) Ok, diagram drawn. It actually does not look that bad, although the two angles and

are quite weird.

- Let the intouch points be

. Then,

passes through the tangency point from

, which we will call

.

- Why am I so tempted to draw the Sharky-Devil point?

- What happens if we draw in the circumcircle of

?

- Why is this actually hard? What even are these angles?? Do I split

? Midpoints and incenter are so weird.

What happens if we draw the line through parallel to

? Let it intersect

,

at

,

. Then,

looks suspiciously like

. If we can prove this, then we are done.

- Wow. I guessed that

and

are similar, and the only way to tell that is if

. Hence, the guess is wrong.

- This means that

and

are isogonal in

.

- By yet more angle chasing,

.

- In particular,

spirals to

.

Now the midpoint seems approachable, because the spiral sends it back to the midpoint of

(call this

), which is the center of

.

- Then,

.

- Could

be similar to

? We just need to bash

.

- It’s true! This is because

, and we can use the chicken feet theorem.

- OK we are probably done.

Note that .

, and we are done by angle chase!

This was a hard Q4, I feel.

(0h45m) Time to read this long, long statement.

- This is quite a funny statement, I kinda like it.

- One easy bound is

, by trying every column. I have a suspicion this might be the best.

- There is no point for Turbo to return to a point if he already knows there’s a monster there.

- What if we just block Turbo’s first 2022 attempts?

- Oh, they must be in different columns… and different rows. This still seems very suspicious though.

This means that for every monster that we discover, we can say for sure that the cells in its row and column are free.

- If we go down the first column to find the monster, then in our next move we can try to use the first column as much as possible, except for three cells where we use column 2. This limits the position of the monster in position 2 to two positions.

- If we keep going, we get a “diagonal” of monsters.

- We are always off by a path by just one or two squares.

Hold up. If we guess three random columns, we can free up enough rows and columns to effectively walk through the whole thing. Hmm. Is ?

- Never mind, I am tripping. This fails if the three monsters are in a “diagonal”.

- On the other hand, if they are not in a diagonal, then we are done.

- What if we dictate monsters to always be on a diagonal, and when Turbo reaches anything on the diagonal we immediately declare it monster?

Put another way, what we can do as Turbo’s enemy is to declare the first square he does not know is free to be monster, and try to keep the monsters in a sort of “diagonal”.

- However, there isn’t really a diagonal, since there are

columns and

rows.

- I would be very surprised if the answer is not

or constant.

(1h20m) I found a construction. Here is the strategy:

- For

, Turbo goes straight down

. They have to be in consecutive rows. Hence, they determine the direction of a “diagonal”.

- WLOG the diagonal is topleft – rightbottom. Then, consider the top left rectangle and the bottom right rectangle. One of them is wider than it is tall. We can thus use the same strategy on this rectangle.

- This means

and

.

Ok, it is time to try small cases for real.

- 2 columns: 2

- 3 columns: 3

- 4 columns: 3! (Just go down columns 2,3. They have to be in consecutive rows. Either ways, we have a complete path.)

- 5 columns: 4 is possible. Is 3 possible? Can we always block the first 3 paths?

Can we strong induct on the enemy’s move as well?

- Here’s an interesting idea: if a cell is a monster, we can mark it’s “cross” safe. However, for rows up and down it (and columns not adjacent to that monster), we can kind of mark it “safe” as well, as if it occupied then we can guarantee a path in the next move.

- What if we change the win condition to reaching either the bottom or the left of the grid? I think this may be easier to induct on, since that is how the board looks after the induction.

(1h50m) OK I think I got it. Let the left column be labelled and the right column be labelled

. Then, for

, put a pseudomonster in column

row

. For

, put a pseudomonster in column

row

. This kind of forms a “wall” of size

.

- Call a rectangle fat if its width is one more than its height.

- Once Turbo reaches any point on this wall, declare there to be a monster there. We then update the wall as follows:

- If the top left (resp. bottom right) rectangle is fat and has width

, Replace it’s pseudomonster with a wall of length

.

- The other rectangle would be a square. We keep it’s pseudomonsters. Note that if Turbo ever ventures into that territory and reaches these square pseudomonsters, we can completely block it off. Hence, we can assume Turbo only makes move on the fat rectangle.

This gives and

.

This confirms that the answer is logarithmic. However, the coefficients don’t match.

- We can improve Turbo’s strategy. While we need to guess two columns at the start, after that we can just keep zooming on the fatter rectangle. This will make us off by a constant factor between both bounds.

- Can we guess the general formula?

- For odd

, if Turbo reaches the middle pseudomonster first, we can delay the decision on the orientation of the diagonal to gain one extra move.

(2h40m) OK this is going nowhere. Let’s just solve first.

- Can the enemy always make Turbo go 4 moves? Suppose we block the very first step he takes. Then, in his next attempt he will have to enter the second row on a different column, so we can block that too.

- Wait… acutally Turbo can finish it in three like this.

- In fact, if Turbo can find the monster in the first row, he can guarantee to finish after two more attempts if he just tries going down its left and right.

- Let’s say Turbo goes through the entire first row to find the monster. The only cases where he cannot guarantee to finish on the first move is when the monster is on the first or fifth column. WLOG it’s the first.

- What happens then? If he tries going down the second column, he may hit a monster on the second row. Then, he will need 2 more attempts.

- This is hard.

(3h30m) WHAT?! After a LOT of bashing, here is a strategy for Turbo in 3 moves.

- if the top left most square is a monster, then we can zigzag down -> left -> down -> … from the third column. This works because if we ever hit a monster, we can turn around in the next attempt and reach the bottom through column 1.

The best part is, this generalises. Such an underwhelming problem. I was so ready to divide and conquer to get some logarithmic result. It’s honestly a miracle I even recovered from the log rabbit hole, and probably many people will get stuck here too.

(3h45m) No time for Q6. What in the world is aquaesulian? I’ll call it good from now on.

- We have the equation

or

. We want to show that

can take finitely many values.

- In fact, it is more than “finitely”, it is “finitely across all good functions”. And we need to find the smallest possible upper bound.

We have that always.

- I think I have an idea of how to get

. Consider

.

- Case 1:

.

- Case 2:

.

- Now if

, then either

or

.

Let be the set of

for which

.

- Obviously,

or

.

- We have

or

.

- If

, so is

.

Can we show ? If it is not, then from

, we mus thave

. Set

, then

.

Let be the set of

for which

.

or

.

- If there exists

, then

for all

. Take

, contradiction.

- Hence we get our first result:

is injective at

.

- We need to find any

.

or

.

- Hence,

for all

. Put

, we get a contradiction.

We now have more progress: and

is injective at

.

or

. Either ways,

. This shows that

is both injective and surjective.

or

.

- If

then either

or

.

- If

then

so

.

- In other words,

is either

or

.

Hence or

.

Let be the set for which

.

- We have

.

- The thing I noticed is: if

then so is

from

.

- Furthermore, if

then

is too from

.

- Hence,

is closed under addition.

- Over

, what does this mean?

- If

, then

. Hence,

.

- If

, then

.

This looks important: if then

constant. For example, if we take some

, then the set

satisfies

for some constant

.

- I guess we need to classify

?

- OK let’s go back to our first idea. Suppose

. Then,

or

.

- If

for some

, then

.

(4h30m) Time’s up! Closing thoughts:

- Q4 is a hard geom for its position. This will probably make the bronze cut off quite low.

- Q5 is so out of place. It’s not a bad problem, but I think it’s quite toxic to put this as P5. More people would probably solve it if it were P4. I cannot get over how the logarithmic solution looks so natural and intuitive.

- In fact, I would argue that if it were a P4, it would have been as difficult as a normal P4. Similarly, if it were a P6, it would have been as difficult as a normal P6. Weird but true?

- Q6 does not look that hard? I kind of feel I’m almost done.

Appendix1

(Post mock) Ok let’s continue the FE.

- If

, then

.

- Taking

where this is true, we get

. This means that

.

- Hence,

. Since

, this means that

Ok nvm those are the same thing.

- The only thing we get from

is

. This is in fact true for all

.

- The only condition that we have not used is

when

.

- If

then

. In fact, they are equal too. So

implies

.

Let’s actually try to construct something non-trivial.

- Suppose

. Then,

for some integer

. Set

.

- Also,

, so we only need to solve for

between 0 and 1.

- In other words, only

with

between

and

matters.

- We have that

or

.

- Let’s say we put

. Then either

(which is impossible) or

, or

.

- Hold up we can do this in general: we have that

or

.

- Set

. Then the second one is true only when

by injectivity.

- Hence

for all

, or

, true even when

.

I’m getting too distracted. Let’s go back to construction.

and

. What can we do?

- Suppose

for a range of

. The problem is that any of it’s differences must have

.

- Suppose we have

for

and

for the rest.

- Unfortunately,

must be

also.

- We cannot have a “range” of

.

- We cannot have a “range” of same

s. This is hard man.

- What if

for non-integer

(between 0 and 1)?

- If

, then

. Wow!

This gives the answer of . Could this be the answer? Perhaps for all

the value

is constant?

- As with above, if

, then

or

.

- Let

also. We just need to find

such that

and

.

Wait! Either or

must work! What just happened…

Most of the stuff above was redundant, but that was a beautiful finish.

- I took about 4 hours total to solve Q6, so I was wrong about being close to finishing. (Perhaps I was close to bounding c=2, but very far from a solution.) The hardest part, of course, is deciding to actually try for a c>1 solution set. ↩︎

Leave a reply to Gabriel Goh Cancel reply