I’ve just finished three weeks of confinement in National Service, and I don’t really want to talk about that so.

It took me around a week to realise that every single uniform (and bag, and helmet) has a different camouflage design. Uniforms are not uniform. And that perplexed me a lot, because if they were pixelated anyways, then what’s the point? Isn’t it more efficient to mass produce identical uniforms?

After much research, I am still nowhere closer to solving that question.1 However, I now know a lot more about military camouflage, and it turned out to be much more interesting than I expected.

Squares

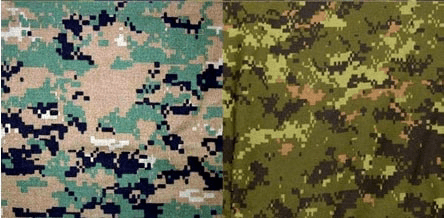

Digitally-produced pixelated camouflage only became mass produced in the early 21st century, when Canada launched CADPAT. This revolutionary design quickly became the archetype for military camouflage, with the US following suit with MARPAT. Over the years, big names like Russia, China, South Korea and India have similarly transformed their uniforms.

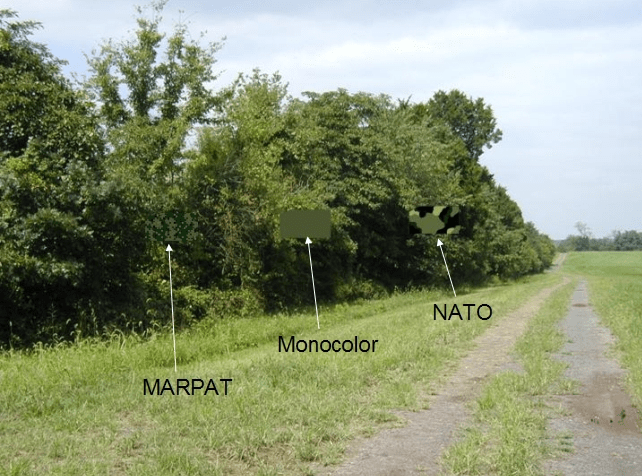

Just how much more effective was digital camo (yea, I’ll just call it that) compared to traditional camouflage? Participants of a survey found that MARPAT took 2.5x longer to detect than the then-widely-used NATO 3-color pattern.

Yes, two and a half.

How? A bit of math, a bit of science, a bit of art.

Fractals

The basic premise that digital camo is based on is pretty simple: camouflage needs to be effective when observed from every distance.

Unfortunately, the eye tends to see different details from different ranges. The solution? Find something that looks the same whether you zoom in or zoom out – a property known as self-similarity. Weird as it sounds, the optimal uniform is essentially a fractal, specifically one that looks the same no matter where you zoom in at.2

In fact, the idea of fractal camouflage (I did not make up that term) has existed since at least WW2. Computers just make it easier to do this at a large scale.

Amusingly, the MARPAT patent has a whole paragraph (column 11) dedicated to approximating the fractal dimension of its design, which happens to be roughly 1.23.

Creating color patches whose roughness (texture) matches the roughness (texture) of the background will provide better concealment than matching only the percentage of each color.

– US Marines

Scales

As it turns out, varying distances are not the only problem.

Humans perceive images in two different ways, known fancifully as the tectopulvinar and geniculostriate pathways (what a mouthful!).

The idea here is very simple: when our eyes see something, two things have happened – our brains figured out where and what it is. Digital camo and its fractal nature disrupts our ability to complete both tasks.

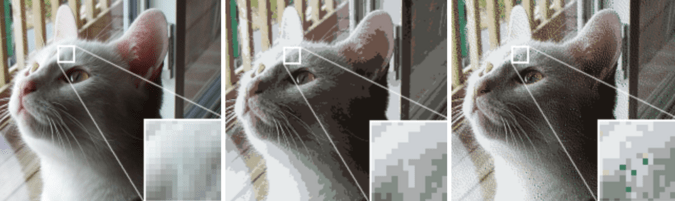

Patterns at a small scale (the pixels3) makes it harder to spot something hidden in a background by mimicking its “texture”. The easiest way to confirm this is to see it for yourself:

Patterns at a large scale distort and breaks the outline of the concealed object, making them harder to recognised even if they are spotted. This technique, known as disruptive colouration, is frequently observed in nature, such as in zebras. Imagine being a predator trying to identify a single zebra in this mess.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/25/9d2512c2-8719-4b0b-b687-9ac702f74389/istock-545671718.jpg)

Using camouflage to trip both of our visual pathways was the brainchild of US army officer and camofleur Timothy O’Neill, who in 1976 invented “Dual-Tex”. One look at the design and it is immediately obvious that Dual-Tex was the precursor to the modern-day digital camo.

Colours

Dithering is a fundamental tool in pixel art. By alternating colours in a checkerboard fashion, we can trick the eye to perceive depth, colours, and blending with a limited amount of pixels.

To do this, intentional errors are added to a pixel image, as seen in this Wikipedia example below:

As it turns out, the pixels in digital camo lead to the exact same effect. A randomly “misplaced” pixel here and there gives an illusion of depth and texture.

This makes it much more effective than say monocolour camouflage, because it mimics the textures and roughness usually found in nature. It also outperforms traditional disruptive coloration designs because dithering removes the presence of distinct lines and hard edges.

Digital camouflage is specifically designed to confuse the human eye by sending out a high spatial frequency component usually missing in traditional patterns.

– Anthony King

It is important to remember that this is not enough to hide in the visible light spectrum. Modern uniforms can be equipped with camouflage from infrared sensors, radar and thermal imaging.

Algorithm

Militaries being militaries, one would naturally expect that algorithms to generate digital camo are classified. Indeed, HyperStealth, the company behind CADPAT, used an algorithm known as C2G (Camouflage Designated Enhanced Fractal Geometry). I couldn’t find any other reference to that on the Internet.

But, as it turns out, the design process for the Netherlands Fractal Pattern is available online.4

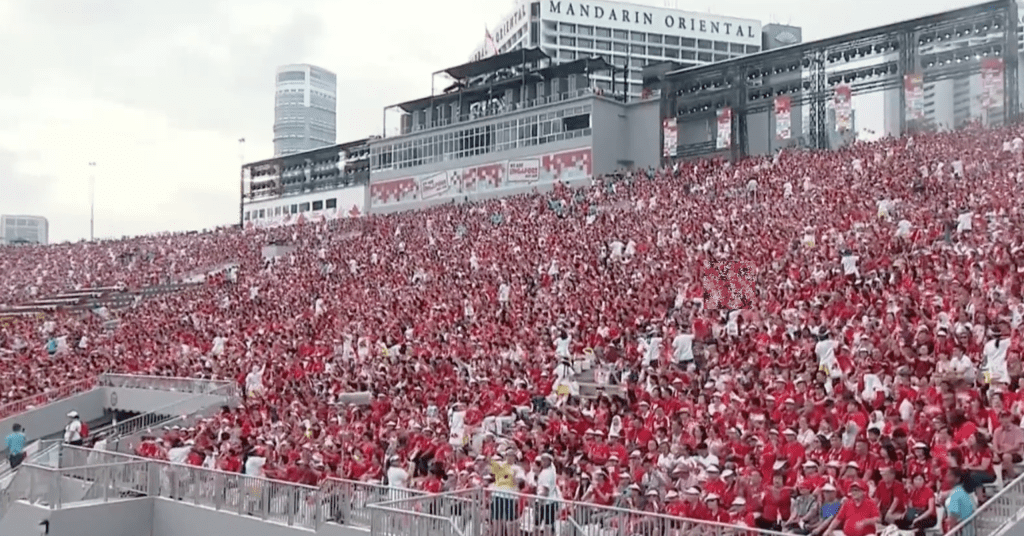

So, suppose I was a sniper targeting VIPs at Singapore’s National Day Parade (purely hypothetically, of course). I need to blend in with the crowds to stay hidden from counter-snipers. What should I wear?

Red and white, of course. But suppose I wanted to camouflage a tank in there or something. Bear with me.

Step 1: create a picture collage of your background

I just googled “NDP audience” and copy pasted a bunch of them together.

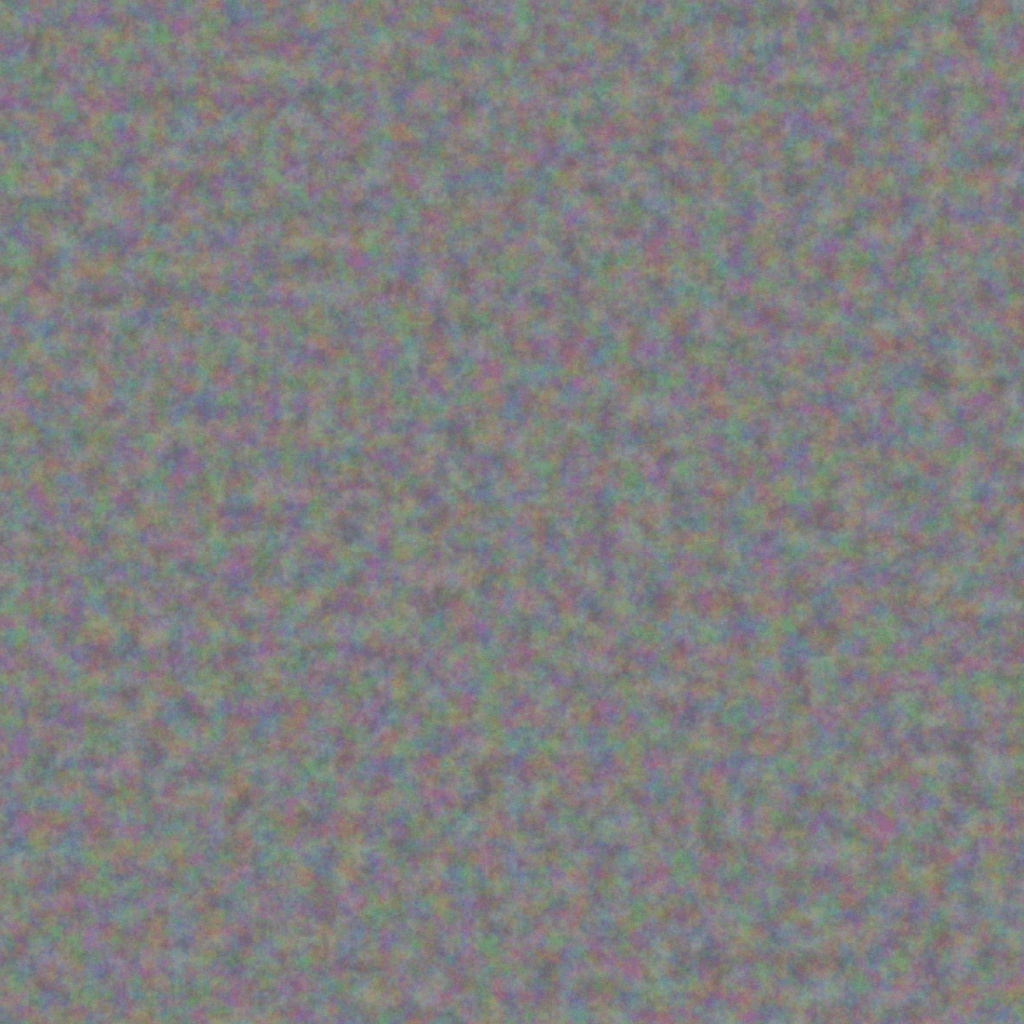

Step 2: Generate a Perlin noise (or any fractal noise) image

I just used this online website. Select “Color”.

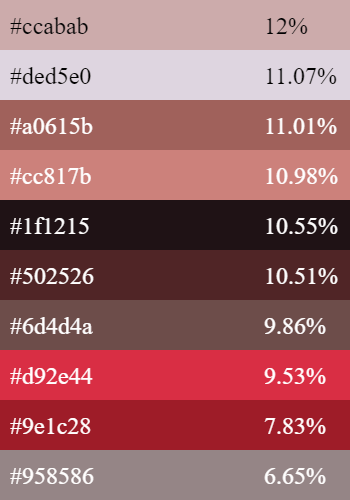

Step 3: Reduce the number of colours in both images

I reduced it to 10, using this online website.

Step 4: Extract the 10 colours

I used another online website.

Step 5: Change the 10 colours on the noise image

I used, guess what, another online website. Set the percentage to 0.

And finally…

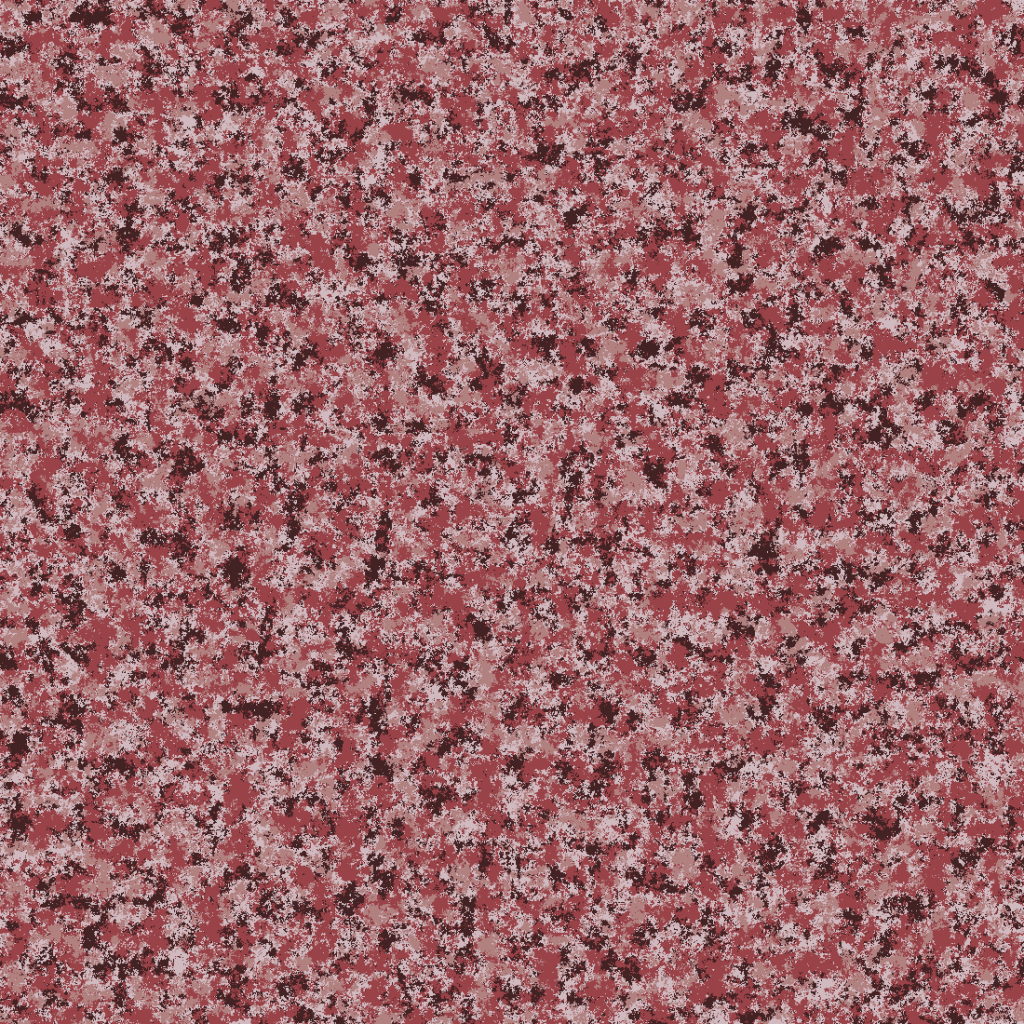

Step 6: Trim the 10 colours down to 4

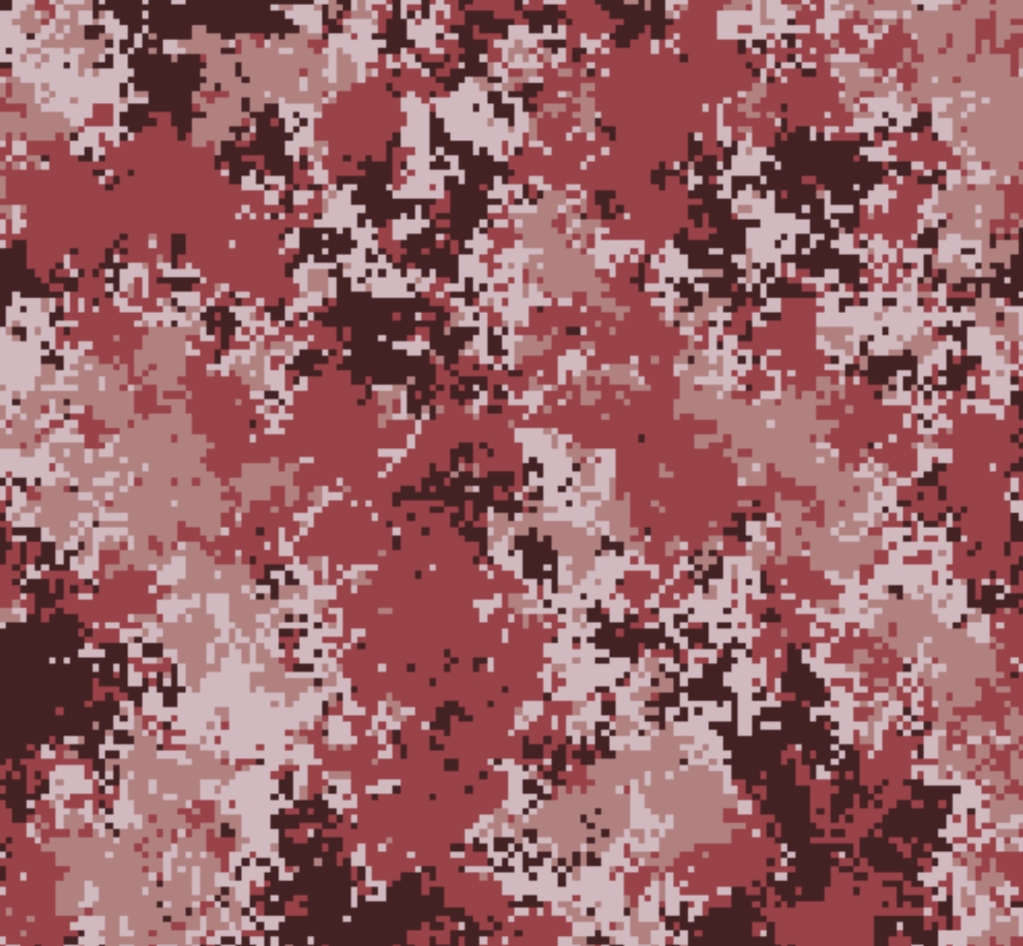

Here’s a zoomed in part of the image:

And we’re done!

Testing

Time to see how effective the camouflage is! The following image looks exactly like the one you’ve seen in the MARPAT test above, except this time with my camouflage at a picture of the NDP. Let’s see how fast you can spot it.

My younger brother took 5 seconds. Not too bad (for me, not for him).

Small aside: when I pondered over how to code my own camo, my initial idea was to randomly fill in a few pixels, and then slowly colour each empty pixel with a high probability of being the same colour as its neighbour. This has been tried before, but turns out to be completely unnecessary.

Thanks for reading!

- My best bet is, you might be able to train a computer (or human) to find a specific pattern, and it isn’t much harder to just randomise it. ↩︎

- There is another big advantage, which is that nature already exhibits a plethora of fractal behaviour, and what better way to blend in with nature than to imitate it? ↩︎

- As it turns out, using squares as opposed to organic shapes don’t make much of a difference, as long as the “fractal principle” is observed. Squares are used simply because they are easier to design and print. ↩︎

- Interestingly, the same article argues that digital camo does not serve much functional purpose, but rather serves as an indication that a military is advanced and in tune with the digital age. ↩︎

Leave a reply to holypotaoto Cancel reply