“Live-solve” / Solution walk-through

Have not been spoiled on the problems, but I have been spoiled on the scores, so I can roughly guess the difficulty of this paper.

Day 1

(0h5m) First thoughts:

- CGN and the geom looks weird. Actually the FE looks weird also.

- Not much else to think about

(0h10m) I tried the smallest case of and seems like only

works. Then, I moved on to

.

-

can be done with the same construction as

.

-

is an interesting case. If we use one of the three lines that covers the most points, then this reduces to

which we have case bashed to shown is not possible

- Kind of feels like there will be some induction here

- What if we don’t use any of the long lines for

? (long meaning covering the most lattice points)

- Since we only get 4 lines to cover 10 points, it has to be

. However all the lines that cover 3 points goes through the center point, hence it is not possible.

- Finally,

is possible because

is possible, and

is not possible because all the lines passing through 3 points are not sunny.

(0h20m) Seems like a sunny line can only clear at most -ish points, and yet the average line has to clear

. This forces some lines to be sunny, but it’s not very helpful. Let’s focus on the induction idea.

- Consider the longest diagonal. If all of them are joined together by one line, then we can use our induction. If not, they each have to be cleared separately on one line. This looks like a very useful result.

- Oh wait, the diagram is symmetric, we have three longest lines to clear. If any of them are selected, then we can induct. Else, each of the

lines need to clear one point from each of the long edges.

- At this point I can feel we are already done. However, some (to be specific 3) of the points lie on multiple edges. How do we deal with that easily? Just count them all together.

(0h30m) Time to formalise the solution

- We have

points on the perimeter. Assuming none of the three longest lines are chosen, each line can only cover 2 of these perimeter points. Hence,

, which resolves to

.

- Hence for all

, one of the three longest lines must be chosen, resolving to the

case.

- Only

works for all

Remarks: I keep getting confused between what is sunny and what is not-sunny. I think this is a very, very good question to put as Q1.

(0h45m) Finished drawing a diagram, which really looks quite unconventional. The tangency also looks quite random.

- We let the tangency point be

. From the diagram, seems like

and

looks suspiciously collinear. This would make the tangency point a lot easier to deal with

- If we define

as the intersection of the lines

, then can we prove that

is concyclic?

- This turns out not to be too hard, because

.

- Wow okay. Now just need to prove the tangency.

(1h0m) Notice that , hence

and

are cyclic. Not sure how helpful that will be.

- As a result,

, so

and

.

- Also as a consequence,

and

are similar.

- That means

. Wait, is

a parallelogram?

- Well yes! Note that

, so

.

(1h15m) In fact, that means that as well due to the parallel lines. Hence, we just need

to bisect

.

- Can we show that

is the incenter of

?

- Since

and

are both perpendicular to

, we have

. So, we just need

, which is true! And we are done.

Remarks: this reminds me of a lot of questions where the proposer has one main point in his full diagram and deliberately crafts the question to hide it. The goal of the solver is then to identify the main point and all the properties it has, and then prove them one by one. He has to stick to one definition and then prove the rest from there, avoiding any circular aguments. One memorable example of this (during NTST) was 2022 G5, but honestly now that I think about it a lot of geom has this concept. Anyways, a bit too easy for a Q2, similar to 2023 Q2.

(1h20m) Q3 is a construct and bound question. We need to find some such that

is relatively big. We begin as usual with all the trivial substitions

gives

gives

which suggests we should focus on primes (wow who would have guessed).

- What if some prime gives 1? What if

in general? Maybe we can prove injectivity at 1? That’s an idea we can try later. Maybe we can prove injectivity in general?

(1h40m) Let’s do a bit of meta thinking. Because the problem is phrased this way, that suggest that we cannot actually find all functions. Furthermore, it is linearly bounded. That means that if we stare hard at , we cannot have

for sufficiently large

, limiting our options to

or

.

- What if

for all

? Then for any

, if we take a sufficiently large

and use FLT,

, which forces

which is of course a solution.

- In fact, this argument also works when there are infinitely many

satisfying

.

- If we combine this logic with the meta-thinking, this means that for any

not the identity, all the large primes must give 1.

- Can we find some way to eliminate

?

(1h50m) Suppose we set . Then, from

we get

. Converting to a

statement using LTE, we get

where

is the order.

- Suppose we pick

such that

but

. This is possible by Dirichlet.

- Suppose

. Then,

and

, a contradiction.

- This implies that

, a very big result.

(2h0m) Suppose that . Then,

. If we only focus on

, then by FLT

as well, and hence if there are infinitely

, we get a contradiction.

Let’s take stock of the situation. We have proven that , and further that if there are infinitely many

that is not 1, then

is the identity. Hence, we are left with one case, that for all sufficiently large

,

.For this case, can we force all

?

(2h10m) If for all sufficiently large primes ,

, then for any other primes

, we have

. This means that

and hence

, a contradiction again by Dirichlet unless

. Hence, for all primes

,

.

- Does something like

and everything else 1 work? Well no.

- How about

and

? Surprisingly, that works! hence

.

- We know that

for all primes larger than 3. Suppose

is odd. Then,

is odd also since it divides

. If it is not 1, then we can find an odd prime

, a contradiction. Hence,

really has to be 1.

- Now it’s about the even numbers. In fact,

cannot have any odd prime factors as well by the same logic, so they must all be powers of 2.

(2h20m) For some even number , we also have

. Surely, that can limit the

of

.

- Note that

, hence

. This is at most 4 times as much as

. Could this work?

- Surprisingly yes! Keeping the construction of even as 4 and odd as 1, but changing

to 16 somehow works because

. And we are done!

Remarks: this really is quite easy for a Q3. Not sure if it is doable without Dirichlet, and I think I overcomplicated some of the arguments here. But hey, if it works it works. Final answer is quite surprising, but if you just ignore getting the answer and solve it like a normal FE, the answer will appear at the end.

More remarks after reading solutions: turns out that for all sufficiently large

is actually a pretty easy thing to get and there was no need for whatever I was doing. Also, it is actually possible to find all functions.

Day 2

(0h5m) Interesting sequence problem. The sequence only breaks when something has less than 3 proper divisors, i.e. it is or

. Obviously we start by trying some cases:

- If

, then the sequence is 6 6 6 …, which works.

- If

, then the sequence is 8 7, fails

- If

, then the sequence is 10 8 7, fails

- In general, the next term will look like

. Not too sure if this is a NT or Alg question but maybe we can do some size bound based on modulo 6 or something?

- The next number that actually works is 18, which also stays constant at 18. Ah, this is because

. Hence, in general, all multiples of 6 that are not multiples of 4 or 5 work.

- To be more mathematical, these are the numbers congruent to

. We call these the steady numbers.

(0h20m) In fact, there are only two ways that , which are the

combo (increase of 13/12) or the

combo (increase of 31/30). Can we use this to generate other numbers that work?

- The first one, using the

combo, will require us to find some solution to

. There is, surprisingly, an answer:

, which leads to the sequence 504 546 546 546 …

- Why does the solution set look so weird? Did I read the question wrong or something?

(0h30m) Anyways, the fact that having both 2 and 3 are the only ways to increase the sequence kind of suggests that we have to start with a multiple of 6. Can we make this rigorous?

- Suppose we have

not a multiple of 2. As mentioned, it will definitely decrease. Can

be a multiple of 2? Since the three smallest divisors

are odd, hence

, hence it cannot be a multiple of 2.

- Now for the non-multiples of 3. In this case we need to show that a non-multiple of 3 can never lead to a multiple of 3.

- If lets say the three smallest divisors are something like

, then we are done as that decreases the number by a factor of 7/8. Surely we can just spam every case?

- I did this on paper and am a bit lazy to type it out, but to prove this claim, we can just clear the cases

(gives an odd number),

(gives a non-multiple of 3),

(gives a non-multiple of 3) as well based on either mod 2 or mod 3.

- This means that the sequence will continue to decrease and cannot be infinite. Thus, every term is a multiple of 6.

- This is good, because for multiples of 6, the next term will never be smaller. This gives us some structure to the sequence.

(0h50m) It seems that we only have to play with the factors of as the rest will remain untouched.

- Consider if we start with

. Then, the next term will be

.

- If we start with

, then the next term will be

. This is not good, because we are left with an odd number. We should thus never have to use the

combo.

- That leaves us with the

combo. If we keep using it, we will be continuously taking out

from the number. At the end, we should be left with one of the steady numbers.

- This allows us to categorise all the possible

s, although it looks quite ugly.

The complete solution set should be where

. What even is this…

Remarks: unfortunately I do not find this nice, as there is no real satisfaction in solving the question, I’m just left with a “did I get this right?” Kind of like 2022 N1 (yes, another NTST question). Difficulty wise, I think it is actually pretty hard for a contestant to nail a 7 point.

(1h0m) Inekoalaty. Nice. Let’s try out some strategies for both Alice and Bazza. For convenience, I will assume Alice is a female and Bazza is a male.

- What if Alice just picks

every time? Then from the first move, if

already, Bazza is doomed. Hence,

is a win for Alice.

- Next, what if

, which means Alice is picking relatively small numbers, but Bazza just picks the largest possible number to explode her bound? I.e. if we always set

? Then

, and hence

. Thus, if

, Bazza wins.

- Wait but pause. How do we know that Bazza can always pick his next term? Well, since at every turn he leaves

, Alice will have to pick something that is

, and so there is always something for Bazza to pick next. This guarantees his victory.

(1h20m) We are now left with the case that . Maybe both of them can guarantee not to lose?

- The intuition works something like this: Alice wants to keep SOS (sum of squares) high but sum low, so she wants the values to have a wide range. Bazza wants to keep SOS low but sum high, so he wants the values to be clustered.

- With this in mind, what if Alice just keeps picking 0 every turn? Then, in order for Bazza to win, we must have

but yet

. In other words,

. Voila. Alice really can guarantee not to lose in this whole range.

- Can Alice force a win by finally picking a very large number? Maybe if

is strictly greater than

?

- Suppose this has gone on for

rounds. We have that

. If we pick the largest possible

, can we guarantee

?

- Well yes! By Cauchy, this will be true for sufficiently large

. Hence, Alice can just play the waiting game and spam zeros until the time is right, and then Bazza will be destroyed.

(1h55m) We have now cleared all cases less , which we have shown Alice can guarantee not to lose. Now for Bazza – in fact we can easily show that our Bazza strategy above allows him not to lose in this case as well. And we are done!

Remarks: I think this is a nice question, even though once again a bit easy for a Q5. The main difficulty lies in getting the correct intuition for what Alice and Bazza wants, and the rest follows naturally.

(2h0m) Very clean statement. We have the obvious bound of , which works no matter which set of points we choose from. It definitely seems like we can do better asymptotically.

- As usual, started with some small cases. However, this feels like the type of question where small cases don’t seem to give a good picture of the general case due to all the local constraints.

- Perhaps it would be better to think of a large square and trying to see how we can stuff in rectangles.

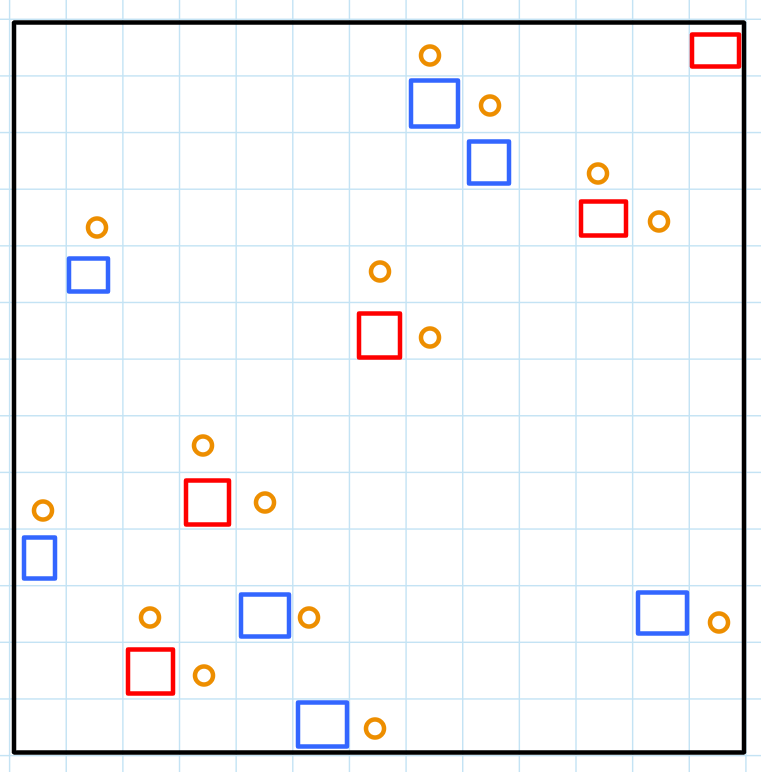

(2h30m) If our empty squares are the main diagonal of the grid, then by considering the adjacent squares to this diagonal, no rectangle can cover both of them. Hence, at least are needed. Maybe we can get the bound by thinking about mutually non-coverable squares? I.e. squares that cannot be covered by a single square (pretty lousy naming, I know, but it kinda makes sense for me intuitively).

- If we just take every square on top of an empty one, that is

squares that are mutually non-coverable. This gives us a bound of

. Can we do better? Maybe using Erdos-Szekeres to find a “staircase”?

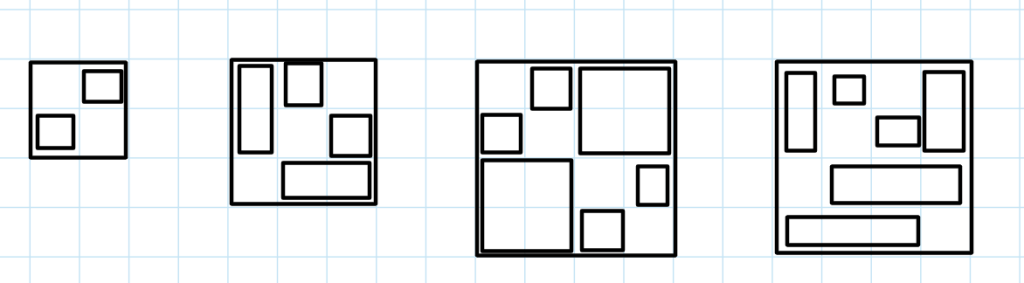

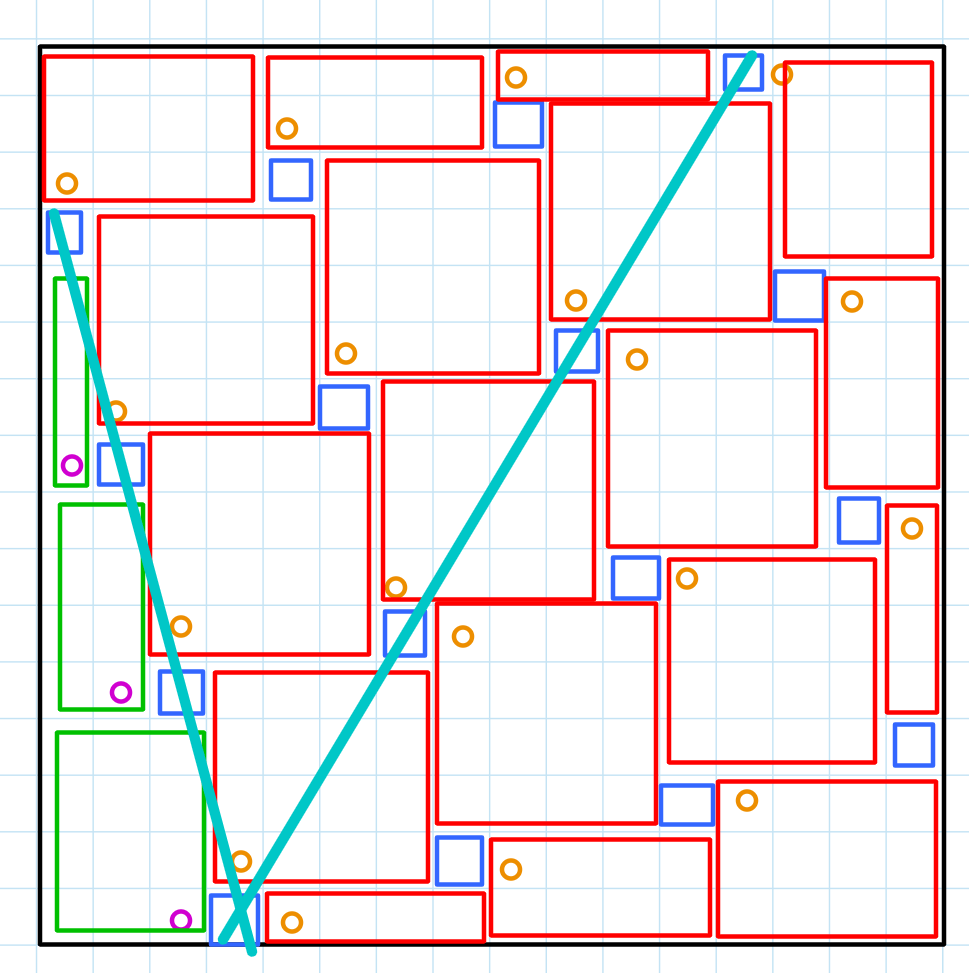

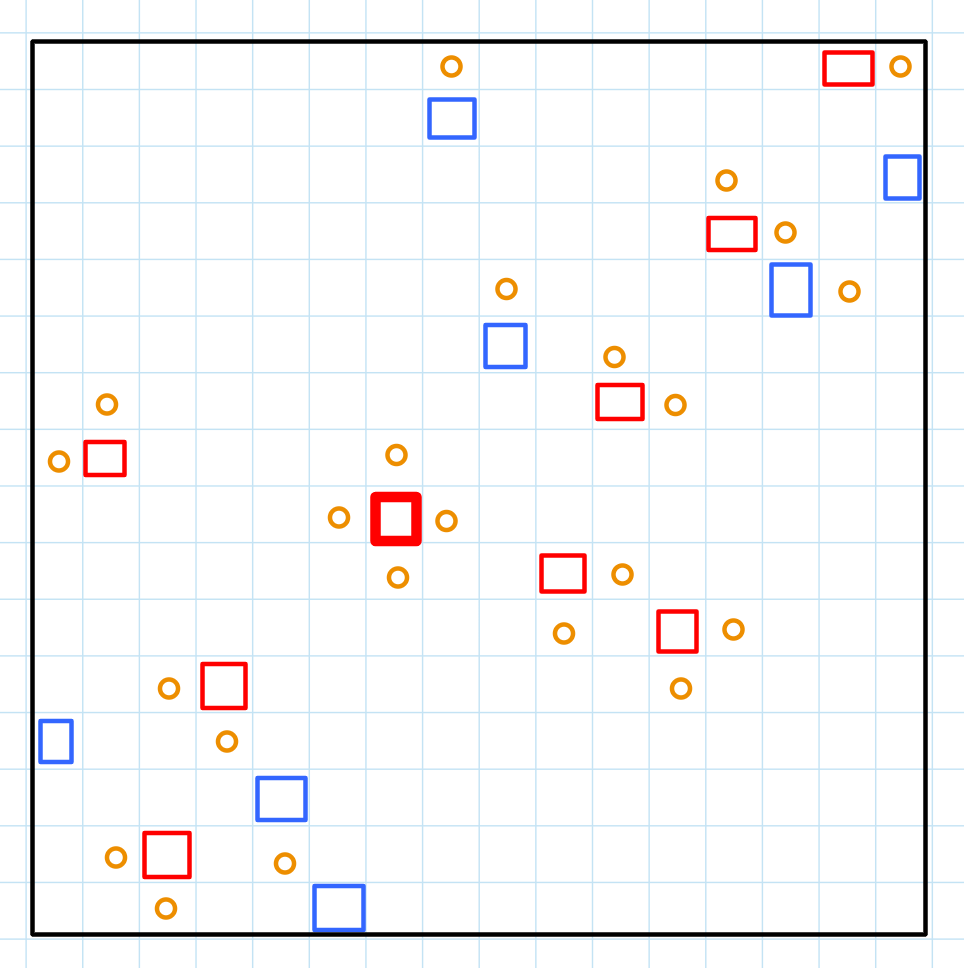

- Suppose we take the longest increasing set of empty squares. In the diagram below, this is marked by the red squares. For each red squares, consider the cell on its direct top and left. For the empty squares above this “diagonal”, consider the cell directly above. For the empty squares on the right of the “diagonal”, consider the cell directly to the right.

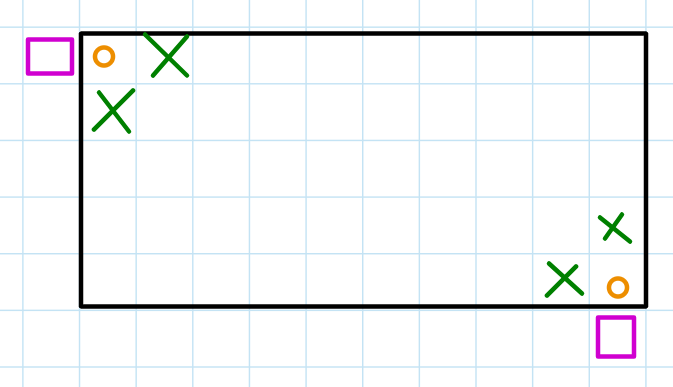

- Is it guaranteed that none of these cells (marked in orange) can be covered by the same rectangle? Suppose it is possible. Then, we must have the case in the diagram below, where there is an empty square at the two purple slots. However, this will never happen in our construction of the orange cells

- How many rectangles does that give us? By Erdos-Szekeres, we have at least

(-2 for the edges). That is a significant improvement from our previous bound. Can we somehow get equality?

- This will mean that our largest possible increasing/decreasing subsequence is exactly

, which is extremely tight as

is a perfect square. Essentially, our empty squares must be a slightly tilted square.

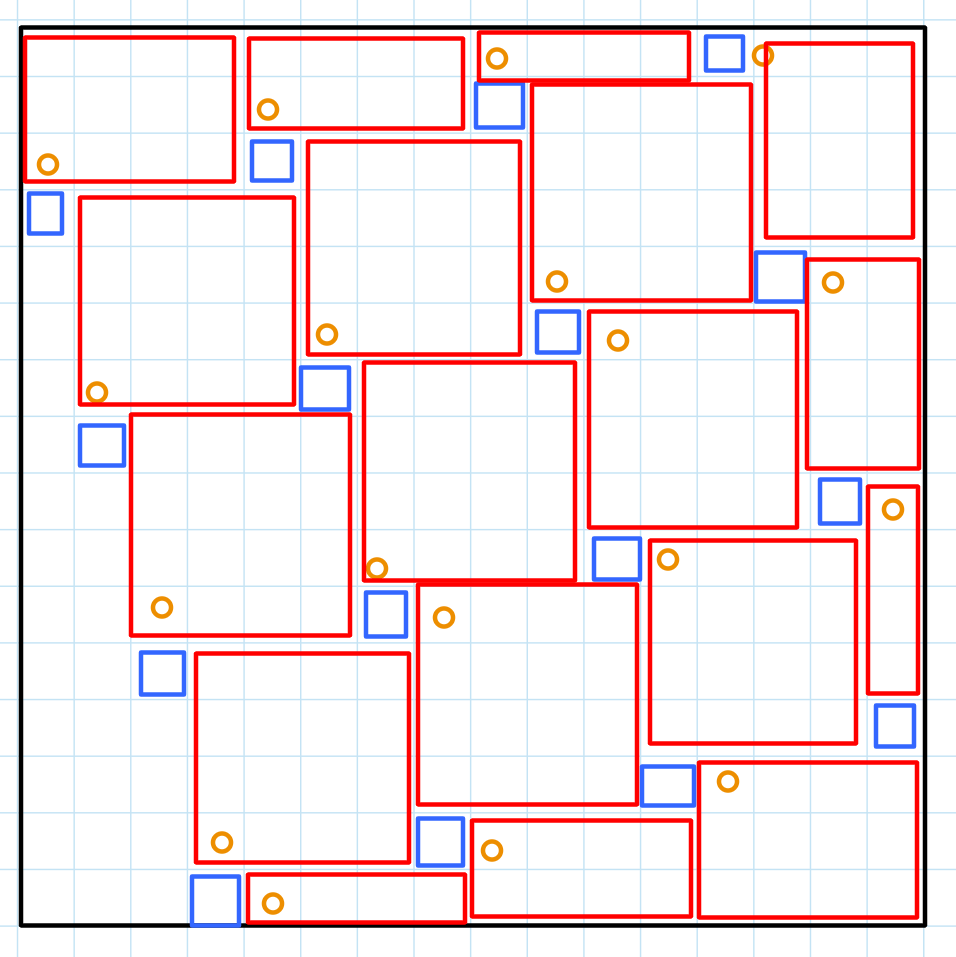

Unfortunately, using the tilted square, we can only get up to the construction below. If we add a few more boxes, this construction gives us

(3h0m) Perhaps we can add more mutually non-coverable squares? For example, the purple ones in the diagram below. Essentially, we need to find a better algorithm to select our mutually non-coverable squares.

If we look at the above, basically we are using the two “line segments” as see below.

- What if I try to find the longest “cross” instead? That will look something like the diagram below.

- This looks promising. Assuming the number of red squares is

, this guarantees, at least

. Hence, we just need

.

(3h30m) Is it possible to show that the sum of the lengths of the longest increasing subsequence and longest decreasing subsequence is at least ? Then, we can combine them together and afford a

at their intersection.

- To do this, we can adapt the original pigeonhole proof of Erdos Szekeres. Suppose the longest increasing sequence has length

and the longest decreasing sequence has length

. Label each square with two numbers

, the length of the longest increasing (resp. decreasing sequence) ending with that square. Then, each pair of labels must be different, leaving only

possible pairs.

- By AM-GM,

, and we are done!

Remarks: I actually think this is a pretty motivatable solution, where one thing leads to another and things kind of just fall into place. The main idea of considering the “mutually un-coverable” squares is a very intuitive idea, and then choosing those next to empty squares is very logical as well. Using the longest increasing subsequence is motivated from the “main diagonal” set of empty squares. Suitable difficulty for a Q6, and looking at the scores I really expected more people to solve it. I wonder what was the main bottleneck…

And that’s it! I think this is the easiest IMO paper to FC in quite a while, even more so than 2022.

Did I make any mistakes? Let me know 🙂

It’s actually insane that there’s an SG problem on the IMO. Congratulations to the proposers!

Leave a comment